After a few weekends of discussing the topic of sustainable living and development with family and friends I have heard the term "moral" or idea of "morality" being expressed over the topic. This led me to discover that many people who discuss or are told about living in a sustainable manner believe that the choice to live sustainable is a moral one. The question of living sustainable is indeed a moral one but is the meat of the choice really moral? What makes it a moral question? What is the necessity of living so? I decided to put a few of the answerers for these questions down to paper.

The morality of living sustainably is simple. As long as we live within the means given to us by nature we will be able to live within nature. This may not be a symbiotic relationship but we can foster a less parasitic relationship with our ecosystem. In taking on a sustainable life we are able to support ourselves without detrimental results on the land around us. But it is not just the land that we are saving by living in a sustainable way. The effects of life the way we live it now are being felt all over the world. Rising seas, rising temperatures, unpredictable climate, degraded agricultural systems, overpopulation, overuse of resources, deforestation, the list goes on. By living in a more sustainable way we can reduce these negative effects of the way life has been lived, making living easier and increasing the likelihood that we will have a place to live in the future.

That brings me to the practical side of the choice to live sustainably. We already talked about the effects of our way of life on the world, so what does that mean for the practicality and moreover the necessity of sustainability. With our agricultural system stretched globally we are limited with what we can expect in the years to come, if we chose to continue on with a global system. The global agricultural system will not hold up under the stresses of reduced fossil fuel inputs and certainly will not survive the continues stresses the system itself puts on the land. Our system is losing thousands if not millions of acres a year to degradation, soil erosion, soil death, loss of water resources, suburban sprawl, etc. If the system we are using is killing the land we need to make the system work then it can clearly not last. If the fossil fuels used to power our system are polluting the word to the point it alters climate for the worse then we cannot further their use. If those same fossil fuel run out over the next 30 years, then we will surely face many years of strife if we dont change our ways. War, famine, climatic upheaval, none of these sound like a way to further life the way we know it.

So again morally we need to change our ways in order to protect our live, the lives of our children and our neighbors for generations to come. In order to do so we will be living a more harmonious life with nature. To anyone peace, harmony, safety for our children, helping our neighbors, protecting our species all seem like morally right and positive ends. From a practical point of view, being able to feed ourselves, live without fearing shortages of food, water, land, resources, electricity, safety from climatic change, and the security of our nation, all seem like necessities.

Through the lens of these two arguments we can see that certainly a portion of the argument is moral but the hard fact of the argument is that it is a necessary change that we must make.

Monday, December 21, 2009

Friday, December 11, 2009

Communes, Intentional Communities, and Ecovillages; different spins on society that can sustain humanity into the future.

When someone tells you they want to live on a commune they immediately have visions of free-loving hippies and psychedelic drug use, the traditional view of anyone counter to the common ideas of how a society should be structured. This, at times, may have been a understandable outlook, the 60's had their ups and downs, but modern intentional communities are paving the way for people to live sustainable into the future.

So what are all these concepts anyway? Communes? Intentional Communities? Ecovillages?

The idea of a commune is nothing new, we are all familiar with the communes of the 60's in America, but they go much further back into history than that. In America there were many political, religious, or social communes that date back into the 1800's. Believe it or not the Oneida silverware company, in Oneida, New York, began as a commune! Abroad there are histories of communes in Europe, in countries like Germany and Russia. In the Middle East was home to communes in the past. All over the world there are Abbey's and Monasteries that are communes and some of these date back hundreds of years, if not more!

What a commune is differs greatly from place to place but most are a community of people who unite over social, political, or religious causes, common interests of goals, and many other things. Typically material possessions and land are shared along with income and resources. These are a type of "intentional community" or planned community. Basically a residential community that places a high emphasis on team work and the common good, and which works towards a better way of life for its residents. Many commune-type communities are ruled democratically or by majority vote of its founding members. However some have a more hierarchical form of rule. It would seem that one common thread is a disdain for bureaucracy and unfairness.

What is an interesting concept within a commune is the idea of shared property and possessions. Foreign to most Americans is the concept that a group can own a piece of property, live and work on that property, and be successful as a society. Even more unusual is the idea that a group of people would pool their individual incomes together in order to serve the interests of the group as a whole. By bringing all their income together into one common purse the group can achieve much more than the individual and in achieving more as a group they raise the standard of living for the whole commune.

I personally think that in a time of global economic hardship the idea that a group could come together like this. In a way it is a very human thing to do. Those in the group without an income could find a way to be beneficial the group through the growing of food and livestock or doing the work and chores around the property, and maintaining the various systems needed for life. Meanwhile those who have an income can bring that into the group and benefit the group as a whole while being supported by other members of the group. This sort of symbiosis, I feel, is lost on many Americans today. Perhaps only in stories and the memories of the very old can we find functioning examples of this in out society.

So then comes the concept of the ecovillage. At it roots a combination of a intentional community and a sustainable habitat for humans. Most ecovillages place special importance on being eco-friendly to the extreme. Green or eco-friendly infrastructure and capital, small ecological footprint, systems of sustainable agriculture such as permaculture, and renewable energy are just some of the pillars that an ecovillage stands on.

Most within ecovillags place a value on being agents of change for the greater society. Setting the example of how people can live without harming the environment. Self-sufficiency is also sometimes a goal but can lead in ways to isolation that may not be desirable. Most ecovillages look down on immoral or objectionable spending from an ecological or socially just point of view. So leave your SUV's at the gate. This mindset of eco-friendliness combined with a goal of making life equally agreeable makes for a very attractive deal.

For more information on ecovillages I encourage you to visit The Ecovillage at Ithaca's website. EVI is a ecovillage made up of two distinct communities with a third on the way in Ithaca, New York. Their village spans a 175 acre parcel of land a large chunk of which is dedicated "green space" that will not be developed. Theirs is a very good inspiration for what a ecovillage looks like.

So how can these examples help our society in the coming decades? It may not be what these communities themselves do within themselves but the example they leave and the skills they teach others that will be of greatest importance to society as a whole. In the face of the converging problems of climate change, peak oil, overpopulation, food scarcity, water shortages, etc, etc, an ecovillage is a small utopia within the greater picture. Expand that Utopian lens to the size of a small town or city and we are talking about a method of living that could possibly sustain society.

A large part of what these ecovillages would do is bring infrastructure, production, agriculture, and all the basics of life back into the local community. Imagine a town of average size where the local economy wasn't a problem because everything that the town needed was made within its own borders. Now the concepts of property and income sharing might not be for all but imagine if your town made its own clothing and you were able to buy that clothing at 80% of what it would cost you to get it from a foreign supplier because by purchasing that piece of clothing you were not only supporting your local textile industry but also your own livelihood. Of course this might not work for places as big as New York City but there are parts of the greater message that might be applicable such as raising your own food, or even just a portion. Within a small town like the many that dot New York State there are surely people who would benefit from the de-specialization of labor, shared property, working within the community, for the community as a community member, growth of local industry, self sufficient lifestyles.

Realistically a group of friends or like minded individuals who were to start such a community would only need to be able to purchase, collectively, a piece of land to suit their group size, maybe 50 acres. From there they would need within their group, individuals with the skills and the means to build homes, farm the land, design green small scale water and water treatment facilities, build a internal power infrastructure, raise livestock. Skills that not many have but that many might be able to learn. Initially such a venture might be costly for those fronting the cash within the group or for all the members of the group equally, but after a few years of hard work and determination they would be able to put together a sustainable habitat for those who lived there. Such a goal is hard met but noble in its intent, and truly any group who deems such a cause worthy is deserving of such a haven. With luck, in time, there may be more such villages in the world. With greater luck perhaps the world will pay attention and set some similar goals of its own.

So what are all these concepts anyway? Communes? Intentional Communities? Ecovillages?

The idea of a commune is nothing new, we are all familiar with the communes of the 60's in America, but they go much further back into history than that. In America there were many political, religious, or social communes that date back into the 1800's. Believe it or not the Oneida silverware company, in Oneida, New York, began as a commune! Abroad there are histories of communes in Europe, in countries like Germany and Russia. In the Middle East was home to communes in the past. All over the world there are Abbey's and Monasteries that are communes and some of these date back hundreds of years, if not more!

What a commune is differs greatly from place to place but most are a community of people who unite over social, political, or religious causes, common interests of goals, and many other things. Typically material possessions and land are shared along with income and resources. These are a type of "intentional community" or planned community. Basically a residential community that places a high emphasis on team work and the common good, and which works towards a better way of life for its residents. Many commune-type communities are ruled democratically or by majority vote of its founding members. However some have a more hierarchical form of rule. It would seem that one common thread is a disdain for bureaucracy and unfairness.

What is an interesting concept within a commune is the idea of shared property and possessions. Foreign to most Americans is the concept that a group can own a piece of property, live and work on that property, and be successful as a society. Even more unusual is the idea that a group of people would pool their individual incomes together in order to serve the interests of the group as a whole. By bringing all their income together into one common purse the group can achieve much more than the individual and in achieving more as a group they raise the standard of living for the whole commune.

I personally think that in a time of global economic hardship the idea that a group could come together like this. In a way it is a very human thing to do. Those in the group without an income could find a way to be beneficial the group through the growing of food and livestock or doing the work and chores around the property, and maintaining the various systems needed for life. Meanwhile those who have an income can bring that into the group and benefit the group as a whole while being supported by other members of the group. This sort of symbiosis, I feel, is lost on many Americans today. Perhaps only in stories and the memories of the very old can we find functioning examples of this in out society.

So then comes the concept of the ecovillage. At it roots a combination of a intentional community and a sustainable habitat for humans. Most ecovillages place special importance on being eco-friendly to the extreme. Green or eco-friendly infrastructure and capital, small ecological footprint, systems of sustainable agriculture such as permaculture, and renewable energy are just some of the pillars that an ecovillage stands on.

Most within ecovillags place a value on being agents of change for the greater society. Setting the example of how people can live without harming the environment. Self-sufficiency is also sometimes a goal but can lead in ways to isolation that may not be desirable. Most ecovillages look down on immoral or objectionable spending from an ecological or socially just point of view. So leave your SUV's at the gate. This mindset of eco-friendliness combined with a goal of making life equally agreeable makes for a very attractive deal.

For more information on ecovillages I encourage you to visit The Ecovillage at Ithaca's website. EVI is a ecovillage made up of two distinct communities with a third on the way in Ithaca, New York. Their village spans a 175 acre parcel of land a large chunk of which is dedicated "green space" that will not be developed. Theirs is a very good inspiration for what a ecovillage looks like.

So how can these examples help our society in the coming decades? It may not be what these communities themselves do within themselves but the example they leave and the skills they teach others that will be of greatest importance to society as a whole. In the face of the converging problems of climate change, peak oil, overpopulation, food scarcity, water shortages, etc, etc, an ecovillage is a small utopia within the greater picture. Expand that Utopian lens to the size of a small town or city and we are talking about a method of living that could possibly sustain society.

A large part of what these ecovillages would do is bring infrastructure, production, agriculture, and all the basics of life back into the local community. Imagine a town of average size where the local economy wasn't a problem because everything that the town needed was made within its own borders. Now the concepts of property and income sharing might not be for all but imagine if your town made its own clothing and you were able to buy that clothing at 80% of what it would cost you to get it from a foreign supplier because by purchasing that piece of clothing you were not only supporting your local textile industry but also your own livelihood. Of course this might not work for places as big as New York City but there are parts of the greater message that might be applicable such as raising your own food, or even just a portion. Within a small town like the many that dot New York State there are surely people who would benefit from the de-specialization of labor, shared property, working within the community, for the community as a community member, growth of local industry, self sufficient lifestyles.

Realistically a group of friends or like minded individuals who were to start such a community would only need to be able to purchase, collectively, a piece of land to suit their group size, maybe 50 acres. From there they would need within their group, individuals with the skills and the means to build homes, farm the land, design green small scale water and water treatment facilities, build a internal power infrastructure, raise livestock. Skills that not many have but that many might be able to learn. Initially such a venture might be costly for those fronting the cash within the group or for all the members of the group equally, but after a few years of hard work and determination they would be able to put together a sustainable habitat for those who lived there. Such a goal is hard met but noble in its intent, and truly any group who deems such a cause worthy is deserving of such a haven. With luck, in time, there may be more such villages in the world. With greater luck perhaps the world will pay attention and set some similar goals of its own.

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

Alternatives in housing, shrinking the McMansion into something small, sustainable, and eco-friendly.

There are a lot of problems with suburbia. One of my least favorite is the McMansions of suburbia, the multitude of cookie cutter, 3000+ square foot, hollow, stick frame, buildings that line countless thousands of housing developments across the nation.

What is so bad about these behemoth buildings? From an architectural stand point they are mutts, cross breeds of many different architectural styles. The facade of many of these homes are considered beautiful but the beauty stops at the front door. Walk around the side of these buildings and they are cold, flat, emotionless, vinyl sided and ugly. There is nothing attractive about vinyl siding. Its cheap plastic, and about as American as housing gets. Under these plastic wrappings are even cheaper stick frame constructions, built to save time, money and labor. On the inside of the massive homes are more of the same; cold, flat, white, and empty spaces. The cheapness of construction in these homes means the house has a short life span and regular repair bill. The insides need to be filled with massive, over-sized, furniture just to make the place feel lived in. There is little to no warmth, no feeling that these houses are homes. These homes are fragile, and hopelessly wasteful in their design and what they incorporate into their construction. This was not always the way, no, in fact our country has a colorful history of building designs and ideas. The alternatives are out there we only need to look for them.

So what are the alternatives? There are many different styles of homes being built today that qualify, at least in my mind, as "alternative' in their designs. These range from the simplest and closest to modern architecture, such as the Tumbleweed Tiny Homes of Jay Shafer, to the very progressive, such as the Earthship designs of Earthship Biotecture. Like I said some of these homes are completely radical and some are rather traditional, either way it is what they represent and how they are built that really makes them special.

Lets start with the Tiny House Movement. Tiny homes are a large piece of American housing history, from the times of the settlers right on up the the bungalows of the early 1900's through the 1970's and beyond to modern cabins and retreats, these sub-1000 square foot homes pop up all over America. But what makes them special, you ask? Efficiency and conservation of space, rooms with multiple uses and features, small operational and construction costs, all of these are part of the tiny house charm.

Here is an example of a tiny house and its floor plan from the Tumbleweed Tiny House Company in California. This particular house is one of their mid range home size wise, and offers up to three bedrooms within it's 681 to 774 square foot structure. They are beautiful homes but they are traditional in their architecture, stick frame with hardwood floors and wood paneled walls and ceilings. However, it is their efficient design scheme, taking advantage of ever little nook and cranny conceivable to fit the necessities of daily life into such a small space. Two bathrooms, the option of three bedrooms, a family room, and kitchen (with an optional dinette area replacing the downstairs bath) all trimmed of the unnecessary space and wasted areas. I know from experience that a family of three or four could easily live in such a small space. It only takes a quick google search to confirm that thousands of families in the US are already living in such simple and streamlined arrangements.

A special aside is needed for Jay Shafer's Tumbleweed Homes that are on wheels. These designs, while dependent on fossil fuel driven trucks, are a novel take on the nomadic lifestyle. Reminiscent of the Gypsy wagons of old Europe, these homes allow for geographic and social mobility on seldom achieved levels. An inspiration to me and many of my friends, these homes exemplify a multitude of alternative concepts in housing.

The next most radical idea in shrinking the McMansion into a sustainable and alternative design again lends much from American housing history, the straw bale home. Building homes with bales of straw dates far back into pre-history, however the use of straw bale construction as an industry or model design is an American invention dating back to the late 1800's. The mid-west was rich with the basic element needed, straw, and it was a staple of local farming. Homes, community buildings, and even churches and schools were constructed out of rectangular straw bales stacked up on top of each other, most famously in the Sand Hills region of Nebraska.

In this method of building there are two schools; those who build straw bale homes with load-bearing straw bale walls and those who build homes with non-load-bearing walls supported by a post and beam style frame. The earliest bale homes were load-bearing. Modern frames bale homes can support as many stories as the builder wishes to put up, though I doubt anything more than seven stories is practical. Any modern home design can be adapted for straw bale construction. Space must be added to accommodate the size of the bales, but the benefit of bale walls is in the limitless artistic possibilities and the R-value (insulation value) of the walls, safety from fire and pests, and costs.

The typical bale wall has as much as triple the R value of a conventional stick framed home, making the straw bale design a pillar of energy savings and efficiency in any environment. The artistic advantage of bale construction is in the ease at which curves, shapes, and complex designs can be integrated into a stawbale home. Your imagination is the limit when you are able to cut and shape the straw to whatever shape you wish and the plaster, with which you cover the bales, can be colored and formed at will. The possibilities are really endless and this uniqueness makes for a very attractive home.

The level fire and pest resistance that a strawbale home provides takes most by storm and leaves most completely blown away when they see facts. A well built straw bale home is nearly fireproof when compared to a typical stick frame structure. If you punched a hole in the wall of a straw bale home and lit the straw with a lighter it can take as much as 24 hours until there is any structural failure. When compared to the minutes it can take to bring down a stick frame home this is truly unbelievable! This is because there is very little air inside the walls of a straw bale home, effectively suffocating any fire.

Quite similarly a well built straw bale home is nearly impervious to pests as there isn't much for them in the densely packed straw and they also have to bore through very hard plaster to get to it.

Lastly the cost of a straw bale home is a huge point to discuss. On average the typical straw bale home costs between $30 and $100 per square foot. This varies greatly depending on things like source of labor, bales, equipment used, number of workers you hire, and permits needed. Of course the lower ranges are typically that low because a person decides to DIY their house under the guidance of an experienced professional and hires family and friends at the cost of pizza and beer on weekends to get the job done. So the cost will obviously go up if you hire a contractor to do it for you. In comparison to a stick frame home, which costs on average $80-$200 per square foot, a straw bale home is a great alternative and remember we haven't discussed the savings over time with such good insulation or the ecological implications of building with straw.

To briefly cover the ecological implications, let me compare the main components of both straw baled and stick frame homes. Straw bales rely on just that, straw bales, which can be regenerated twice a year. Stick frame homes rely on 2x4's and other lumber, which can only be regenerated once every 6-8 years or longer. Then we may consider the interior and exterior walls. A straw bale is covered, inside and out, with plaster (plaster, stucco, etc) made from; a mix of cement, lime formula, or clay/earth, all readily available and cheap to procure. A stick frame home is reliant on Sheetrock and vinyl siding, both of which are artificial and costly to produce compared to the coverings on straw bales.

Similar to the straw bale home is the cob home. The cob home is made of a slurry of clay, earth, straw, sand, and water, indeed it is cobbed together! Even cheaper than a straw bale it rivals the straw bales artistic possibilities and in construction is very akin to the adobe construction methods of the South West. Many cob homes, like their straw bale cousins, last for generations on generations. However, the cob home surpasses the straw bale in overall longevity with one of the oldest cob homes still inhabited today at over 500 years old. Adaptable to many climates the cob home has been seen in places like the UK, colonial America, the American South West, Africa, the Middle-East, New Zealand, Australia, and the list goes on and on. My expertise and experience with cob building is very limited, as seen by my short mention of it here, however a short google search will turn up an endless amount of information on the topic. Should you want to visit a cob home, I believe there is still one in construction on the Pine Lake Environmental Campus of Hartwick College, in Oneonta New York. I suggest contacting Peter Blue through Hartwick's website for more information. If you end up there be sure to visit the beautiful example of a straw bale home also at the Pine Lake Campus.

Next up on my list of housing alternatives is the completely sustainable living system of the Earthship. The Earthship is a completely self contained example of what living could be. Developed by the company Earthship Biotechture the Earthship is a system or ideology of building a home. It's design is aimed at providing for the occupant in every conceivable way, from self contained sewage treatment, to solar and wind power for electricity and rain catchment cisterns for a water source. These look and feel almost like a modernized version of the "Hobbit Hole" from J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. These fantastic designs are more than many could imagine and with the ability to be adapted for any climate and condition, constructed of any recycled or renewable material, and containing almost every necessity of life (not to mention all the necessities of modern life). I am not much more than a fan of the Earthship design and my research into this building practice is limited. There is a wealth of information on the Earthships site including diagrams, videos, messages from Earthship inhabitants, amongst other things. It is well worth looking into. My only concern with this concept is the price point. At or above $200 per square foot this is a comparatively expensive concept, at least at the beginning. However, once you actually are living in your Earthship there is very little maintenance and expenses typically encountered with most modern homes, making these homes a valuable investment.

I hope this post was enlightening for you all an I encourage you to comment! If you want me to explore any of the above alternatives or wish to hear about how they can be successfully combined please let me know.

What is so bad about these behemoth buildings? From an architectural stand point they are mutts, cross breeds of many different architectural styles. The facade of many of these homes are considered beautiful but the beauty stops at the front door. Walk around the side of these buildings and they are cold, flat, emotionless, vinyl sided and ugly. There is nothing attractive about vinyl siding. Its cheap plastic, and about as American as housing gets. Under these plastic wrappings are even cheaper stick frame constructions, built to save time, money and labor. On the inside of the massive homes are more of the same; cold, flat, white, and empty spaces. The cheapness of construction in these homes means the house has a short life span and regular repair bill. The insides need to be filled with massive, over-sized, furniture just to make the place feel lived in. There is little to no warmth, no feeling that these houses are homes. These homes are fragile, and hopelessly wasteful in their design and what they incorporate into their construction. This was not always the way, no, in fact our country has a colorful history of building designs and ideas. The alternatives are out there we only need to look for them.

So what are the alternatives? There are many different styles of homes being built today that qualify, at least in my mind, as "alternative' in their designs. These range from the simplest and closest to modern architecture, such as the Tumbleweed Tiny Homes of Jay Shafer, to the very progressive, such as the Earthship designs of Earthship Biotecture. Like I said some of these homes are completely radical and some are rather traditional, either way it is what they represent and how they are built that really makes them special.

Lets start with the Tiny House Movement. Tiny homes are a large piece of American housing history, from the times of the settlers right on up the the bungalows of the early 1900's through the 1970's and beyond to modern cabins and retreats, these sub-1000 square foot homes pop up all over America. But what makes them special, you ask? Efficiency and conservation of space, rooms with multiple uses and features, small operational and construction costs, all of these are part of the tiny house charm.

Here is an example of a tiny house and its floor plan from the Tumbleweed Tiny House Company in California. This particular house is one of their mid range home size wise, and offers up to three bedrooms within it's 681 to 774 square foot structure. They are beautiful homes but they are traditional in their architecture, stick frame with hardwood floors and wood paneled walls and ceilings. However, it is their efficient design scheme, taking advantage of ever little nook and cranny conceivable to fit the necessities of daily life into such a small space. Two bathrooms, the option of three bedrooms, a family room, and kitchen (with an optional dinette area replacing the downstairs bath) all trimmed of the unnecessary space and wasted areas. I know from experience that a family of three or four could easily live in such a small space. It only takes a quick google search to confirm that thousands of families in the US are already living in such simple and streamlined arrangements.

A special aside is needed for Jay Shafer's Tumbleweed Homes that are on wheels. These designs, while dependent on fossil fuel driven trucks, are a novel take on the nomadic lifestyle. Reminiscent of the Gypsy wagons of old Europe, these homes allow for geographic and social mobility on seldom achieved levels. An inspiration to me and many of my friends, these homes exemplify a multitude of alternative concepts in housing.

The next most radical idea in shrinking the McMansion into a sustainable and alternative design again lends much from American housing history, the straw bale home. Building homes with bales of straw dates far back into pre-history, however the use of straw bale construction as an industry or model design is an American invention dating back to the late 1800's. The mid-west was rich with the basic element needed, straw, and it was a staple of local farming. Homes, community buildings, and even churches and schools were constructed out of rectangular straw bales stacked up on top of each other, most famously in the Sand Hills region of Nebraska.

In this method of building there are two schools; those who build straw bale homes with load-bearing straw bale walls and those who build homes with non-load-bearing walls supported by a post and beam style frame. The earliest bale homes were load-bearing. Modern frames bale homes can support as many stories as the builder wishes to put up, though I doubt anything more than seven stories is practical. Any modern home design can be adapted for straw bale construction. Space must be added to accommodate the size of the bales, but the benefit of bale walls is in the limitless artistic possibilities and the R-value (insulation value) of the walls, safety from fire and pests, and costs.

The typical bale wall has as much as triple the R value of a conventional stick framed home, making the straw bale design a pillar of energy savings and efficiency in any environment. The artistic advantage of bale construction is in the ease at which curves, shapes, and complex designs can be integrated into a stawbale home. Your imagination is the limit when you are able to cut and shape the straw to whatever shape you wish and the plaster, with which you cover the bales, can be colored and formed at will. The possibilities are really endless and this uniqueness makes for a very attractive home.

The level fire and pest resistance that a strawbale home provides takes most by storm and leaves most completely blown away when they see facts. A well built straw bale home is nearly fireproof when compared to a typical stick frame structure. If you punched a hole in the wall of a straw bale home and lit the straw with a lighter it can take as much as 24 hours until there is any structural failure. When compared to the minutes it can take to bring down a stick frame home this is truly unbelievable! This is because there is very little air inside the walls of a straw bale home, effectively suffocating any fire.

Quite similarly a well built straw bale home is nearly impervious to pests as there isn't much for them in the densely packed straw and they also have to bore through very hard plaster to get to it.

Lastly the cost of a straw bale home is a huge point to discuss. On average the typical straw bale home costs between $30 and $100 per square foot. This varies greatly depending on things like source of labor, bales, equipment used, number of workers you hire, and permits needed. Of course the lower ranges are typically that low because a person decides to DIY their house under the guidance of an experienced professional and hires family and friends at the cost of pizza and beer on weekends to get the job done. So the cost will obviously go up if you hire a contractor to do it for you. In comparison to a stick frame home, which costs on average $80-$200 per square foot, a straw bale home is a great alternative and remember we haven't discussed the savings over time with such good insulation or the ecological implications of building with straw.

To briefly cover the ecological implications, let me compare the main components of both straw baled and stick frame homes. Straw bales rely on just that, straw bales, which can be regenerated twice a year. Stick frame homes rely on 2x4's and other lumber, which can only be regenerated once every 6-8 years or longer. Then we may consider the interior and exterior walls. A straw bale is covered, inside and out, with plaster (plaster, stucco, etc) made from; a mix of cement, lime formula, or clay/earth, all readily available and cheap to procure. A stick frame home is reliant on Sheetrock and vinyl siding, both of which are artificial and costly to produce compared to the coverings on straw bales.

Similar to the straw bale home is the cob home. The cob home is made of a slurry of clay, earth, straw, sand, and water, indeed it is cobbed together! Even cheaper than a straw bale it rivals the straw bales artistic possibilities and in construction is very akin to the adobe construction methods of the South West. Many cob homes, like their straw bale cousins, last for generations on generations. However, the cob home surpasses the straw bale in overall longevity with one of the oldest cob homes still inhabited today at over 500 years old. Adaptable to many climates the cob home has been seen in places like the UK, colonial America, the American South West, Africa, the Middle-East, New Zealand, Australia, and the list goes on and on. My expertise and experience with cob building is very limited, as seen by my short mention of it here, however a short google search will turn up an endless amount of information on the topic. Should you want to visit a cob home, I believe there is still one in construction on the Pine Lake Environmental Campus of Hartwick College, in Oneonta New York. I suggest contacting Peter Blue through Hartwick's website for more information. If you end up there be sure to visit the beautiful example of a straw bale home also at the Pine Lake Campus.

Next up on my list of housing alternatives is the completely sustainable living system of the Earthship. The Earthship is a completely self contained example of what living could be. Developed by the company Earthship Biotechture the Earthship is a system or ideology of building a home. It's design is aimed at providing for the occupant in every conceivable way, from self contained sewage treatment, to solar and wind power for electricity and rain catchment cisterns for a water source. These look and feel almost like a modernized version of the "Hobbit Hole" from J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. These fantastic designs are more than many could imagine and with the ability to be adapted for any climate and condition, constructed of any recycled or renewable material, and containing almost every necessity of life (not to mention all the necessities of modern life). I am not much more than a fan of the Earthship design and my research into this building practice is limited. There is a wealth of information on the Earthships site including diagrams, videos, messages from Earthship inhabitants, amongst other things. It is well worth looking into. My only concern with this concept is the price point. At or above $200 per square foot this is a comparatively expensive concept, at least at the beginning. However, once you actually are living in your Earthship there is very little maintenance and expenses typically encountered with most modern homes, making these homes a valuable investment.

I hope this post was enlightening for you all an I encourage you to comment! If you want me to explore any of the above alternatives or wish to hear about how they can be successfully combined please let me know.

Friday, December 4, 2009

By Request: Holidays in America, why don't I get Kwanzaa off from uni?

This could be a new direction for my fledgling blog, accepting requests to rant on about, but we shall see how people respond to this one before I make it a habit.

Well today's post is all about holidays in America and what we recognize as a federal, local, school, or university holiday. Read this post as a response to someone complaining about why they don't get their religions holy days or holidays off as a regular thing over the holidays celebrated by Christianity, the dominant religion in America.

Let us first consider what holidays we do get off as a regular thing in our schools. I want to look at this in specific because it would seem like the majority of the complaints come from this age group. Lets kick things off with a little analysis of what days we DO get off. Here is a run down of the days the school I am currently working for gets off.

Labor Day

Yom Kippur

Columbus Day

Veterans' Day

Thanksgiving (2 days)

Winter Recess (read Christmas and New Years, 7 days)

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day

Mid-Winter Recess/ Presidents' Day (5 days)

Spring Break/ Easter and Good Friday (6 days)

Memorial Day

For a grand total of 26 days off, not too shabby. What about the holidays that this school recognizes but doesn't observe as days off?

Rosh Hashanah

Id al-Fitr

Passover (2 days)

Muslim New Year's Day

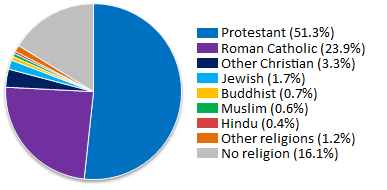

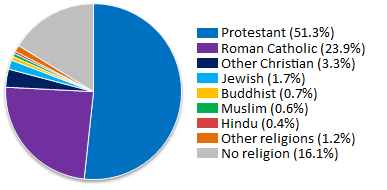

That's an extra five days, not really a big deal, but what other major holidays are left out? To figure this out, first we need to see what our major religions are here in America. To this I move to the ever-trusty Wikipedia.

According to this graph from Wikipedia, Christian religions make up an overwhelming majority of the population in this country, to the tune of 78.5%. We already celebrate most of the major Christian holidays. This makes sense, understandably, as the founding fathers of our dear country fled to America to escape religious prosecution. Huguenots, Anglicans, Dutch Reformed, Quakers, and Puritans made up the bulk of the early settlers in America, ALL escaping from persecution in Europe during the mid 1500's and early 1600's. The Roman Catholics pre-date all of these groups by settling in Puerto Rico during the late 1400's when Columbus came to this side of the pond.

So that covers why we celebrate Christian holidays, sure, but what about the rest of us?

The Jews make up the next largest religion in the United States, coming in at a whopping 1.7%. First appearing on the scene as early as the 1600's, the Jewish community really didn't make more than a ripple in the religious pool of America until the mid 1800's. The only major holidays that are not recognized by most schools and universities is Hanukkah which comes close to Christmas many years. Those eight crazy nights however are not observed as days off. The addition of those eight days to most holiday schedules of schools and uni's would bring the typical winter break to 15 days. If there are any Jewish readers who say I missed something, do let me know, I will add it to my dialog.

According to the graph I am using Buddhism is the next largest religion at a zen-like .7%. Buddhism is one of the religious late-comers to America, landing in the mid-1800's with Asian immigrants from China and elsewhere. I'm no big Buddhist buff, but from what I understand the holy days of Buddhism follow lunar cycles and beyond those monthly celebrations there are also roughly a dozen holidays. Because of my lack of knowledge I'm not going to comment further for fear of sounding like an ignorant boob.

Islam is a fast growing religion in the US, and I an almost guarantee that since the 2007 survey that pegged the Muslim population at .6% it has grown, likely overcoming Buddhism and then some. Major observances of Islam include; Ramadan, the date of which varies year to year, Ashura, Laylat al-Qadr, Laylat ul Isra and Mi'raj, Laylat ul Bara'ah, Eid al-Fitr (last day of Ramadan, 3 day feast), and Eid al-Adha (4 days). The nice thing about Muslim holidays and observances are mostly at night. The word "Laylat" means night or night of, so you can see that most of these wouldn't require a day off. Ramadan is a month of fasting and prayer, which also wouldn't require a month of days off. Both Eid's would require time off but would likely amount to something similar to a 3 or 4 day weekend. Ashura is a two day holiday that coincides with Yom Kippur. So the total count for new holidays to accommodate Muslim holidays would be as many as 8 or 9 depending on the year.

Hinduism is a very small religion in America with only .4% of the population. Hindu holidays number close to 30 and some are based on solar cycles, others are specific days of months of celebration. I am not too firm on Hinduism and its specifics so I will not comment on it however it is easy to say that the roughly 1.25 million Hindu's in American will get by with taking days off from work that they find to be of great importance.

Lastly we have a large group of Americans, the non-affiliated, who make up 16.1% of the population. Larger than any of the other groups in America. These folks, I can say with out a reasonable amount of doubt, don't really care or don't really mind not getting special holidays for them. They are probably good enough to have the days they already have off, off.

So what would it mean to accommodate all these different religions? Well to start we would need to add around 16 to 20 days to the calendar. Wow that's nearly an extra month of school off and the same tacked onto the school year to make up for it! Lets imagine the cost. I don't have good numbers on this but I remember from college hearing that the average public school tuition would work out to almost 10k per student per year. So for 180 school days, the average public school is spending about $55 per student per day. This would mean an additional $1100 per student per year, bringing the average cost per student to near $11,100 per year. The average American school district serves about 1800 students, small I know, but when you consider the number of rural districts this is understandable. Ok enough number juggling. The cost per school to observe as many holidays as politically correct, would be about 2 million dollars.

Now consider the effect this would have on districts that already cannot afford to stay open! Thousands of schools would close, thousands more teachers would be out of a job, and students would need to be crammed into classes in the remaining schools. This would not be the effect everywhere but we would see a dramatic decline in the quality of education for our students.

Take into account I haven't addressed any of the socio-political and socio-economic effects or the effects on the many aspects of American life there would be.

So can we observe the holidays of every religion here in the United States, no. Should we consider it a problem, I think not. Are there more pressing social issues that we need to address, yes our time and money and brain power should be aimed elsewhere.

Well today's post is all about holidays in America and what we recognize as a federal, local, school, or university holiday. Read this post as a response to someone complaining about why they don't get their religions holy days or holidays off as a regular thing over the holidays celebrated by Christianity, the dominant religion in America.

Let us first consider what holidays we do get off as a regular thing in our schools. I want to look at this in specific because it would seem like the majority of the complaints come from this age group. Lets kick things off with a little analysis of what days we DO get off. Here is a run down of the days the school I am currently working for gets off.

Labor Day

Yom Kippur

Columbus Day

Veterans' Day

Thanksgiving (2 days)

Winter Recess (read Christmas and New Years, 7 days)

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day

Mid-Winter Recess/ Presidents' Day (5 days)

Spring Break/ Easter and Good Friday (6 days)

Memorial Day

For a grand total of 26 days off, not too shabby. What about the holidays that this school recognizes but doesn't observe as days off?

Rosh Hashanah

Id al-Fitr

Passover (2 days)

Muslim New Year's Day

That's an extra five days, not really a big deal, but what other major holidays are left out? To figure this out, first we need to see what our major religions are here in America. To this I move to the ever-trusty Wikipedia.

According to this graph from Wikipedia, Christian religions make up an overwhelming majority of the population in this country, to the tune of 78.5%. We already celebrate most of the major Christian holidays. This makes sense, understandably, as the founding fathers of our dear country fled to America to escape religious prosecution. Huguenots, Anglicans, Dutch Reformed, Quakers, and Puritans made up the bulk of the early settlers in America, ALL escaping from persecution in Europe during the mid 1500's and early 1600's. The Roman Catholics pre-date all of these groups by settling in Puerto Rico during the late 1400's when Columbus came to this side of the pond.

So that covers why we celebrate Christian holidays, sure, but what about the rest of us?

The Jews make up the next largest religion in the United States, coming in at a whopping 1.7%. First appearing on the scene as early as the 1600's, the Jewish community really didn't make more than a ripple in the religious pool of America until the mid 1800's. The only major holidays that are not recognized by most schools and universities is Hanukkah which comes close to Christmas many years. Those eight crazy nights however are not observed as days off. The addition of those eight days to most holiday schedules of schools and uni's would bring the typical winter break to 15 days. If there are any Jewish readers who say I missed something, do let me know, I will add it to my dialog.

According to the graph I am using Buddhism is the next largest religion at a zen-like .7%. Buddhism is one of the religious late-comers to America, landing in the mid-1800's with Asian immigrants from China and elsewhere. I'm no big Buddhist buff, but from what I understand the holy days of Buddhism follow lunar cycles and beyond those monthly celebrations there are also roughly a dozen holidays. Because of my lack of knowledge I'm not going to comment further for fear of sounding like an ignorant boob.

Islam is a fast growing religion in the US, and I an almost guarantee that since the 2007 survey that pegged the Muslim population at .6% it has grown, likely overcoming Buddhism and then some. Major observances of Islam include; Ramadan, the date of which varies year to year, Ashura, Laylat al-Qadr, Laylat ul Isra and Mi'raj, Laylat ul Bara'ah, Eid al-Fitr (last day of Ramadan, 3 day feast), and Eid al-Adha (4 days). The nice thing about Muslim holidays and observances are mostly at night. The word "Laylat" means night or night of, so you can see that most of these wouldn't require a day off. Ramadan is a month of fasting and prayer, which also wouldn't require a month of days off. Both Eid's would require time off but would likely amount to something similar to a 3 or 4 day weekend. Ashura is a two day holiday that coincides with Yom Kippur. So the total count for new holidays to accommodate Muslim holidays would be as many as 8 or 9 depending on the year.

Hinduism is a very small religion in America with only .4% of the population. Hindu holidays number close to 30 and some are based on solar cycles, others are specific days of months of celebration. I am not too firm on Hinduism and its specifics so I will not comment on it however it is easy to say that the roughly 1.25 million Hindu's in American will get by with taking days off from work that they find to be of great importance.

Lastly we have a large group of Americans, the non-affiliated, who make up 16.1% of the population. Larger than any of the other groups in America. These folks, I can say with out a reasonable amount of doubt, don't really care or don't really mind not getting special holidays for them. They are probably good enough to have the days they already have off, off.

So what would it mean to accommodate all these different religions? Well to start we would need to add around 16 to 20 days to the calendar. Wow that's nearly an extra month of school off and the same tacked onto the school year to make up for it! Lets imagine the cost. I don't have good numbers on this but I remember from college hearing that the average public school tuition would work out to almost 10k per student per year. So for 180 school days, the average public school is spending about $55 per student per day. This would mean an additional $1100 per student per year, bringing the average cost per student to near $11,100 per year. The average American school district serves about 1800 students, small I know, but when you consider the number of rural districts this is understandable. Ok enough number juggling. The cost per school to observe as many holidays as politically correct, would be about 2 million dollars.

Now consider the effect this would have on districts that already cannot afford to stay open! Thousands of schools would close, thousands more teachers would be out of a job, and students would need to be crammed into classes in the remaining schools. This would not be the effect everywhere but we would see a dramatic decline in the quality of education for our students.

Take into account I haven't addressed any of the socio-political and socio-economic effects or the effects on the many aspects of American life there would be.

So can we observe the holidays of every religion here in the United States, no. Should we consider it a problem, I think not. Are there more pressing social issues that we need to address, yes our time and money and brain power should be aimed elsewhere.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)